Happy New Year! January heralds the opening of the UK National Student Survey (NSS).

The NSS is often thought of as an academic performance measure, but it isn’t: it’s a whole-institution experience measure, yet for the most part it runs as if only academics exist; strategy, planning, and discourses tend to exclude non-academics (unless there are shortcomings when the results are published – at which point, professional services teams can often find themselves accountable for a raft of tenuous metrics).

In this blog post, I draw on my experience to describe why this is problematic, and reflect on how institutions can connect technicians and other professional services teams to work collaboratively to improve the student experience. I conclude by briefly outlining a professional development course that I have written for institutions to help connect and engage non-academics (it has been written for technicians but is applicable more broadly) with the NSS. More detail can be found here: https://www.timsavageconsulting.co.uk/training.

The NSS can be somewhat of a paradox. Technicians aren’t named, but their contribution is everywhere in the data. There is no ‘How well have you been taught and supported in your learning by the technicians?’ question, and so the contribution, performance, and impact of this sizable percentage of the workforce (as measured through the reported experiences of students) must be gleaned from the other survey metrics, and pieced together with the qualitative feedback that accompanies the numerical satisfaction indicators. This isn’t always something that universities are keen to do, because it takes time, effort, and understanding of the breadth of technical roles and responsibilities. It can also shine the light of accountability into unwelcome spaces. So, it can be much easier to cut clear lines through the survey and attribute learning and teaching questions to academic teams, with access to specialist resources/IT and libraries falling to the professional services. However, I should note that whether technicians are categorised as an ‘academic function’ or ‘professional service’ is somewhat of a sector variable.

While this is an easy approach, it’s certainly not the optimal one. And, having an informed, credible, and fit-for-purpose NSS strategy is a mission-critical activity. The NSS drives so many institutional and sector performance indicators (not least reputation and recruitment, league table position, and TEF performance – all of which are highly consequential and, in some instances, existential). Accordingly, low scores are a huge flashing red light on the dashboard of senior leaders in HE and it’s common for courses with low NSS scores to be formally tasked with explaining their underperformance, describe legitimate mitigations, and set out action plans of the SMART variety to improve student experience (and NSS scores) in the next round.

However, in my experience, the resulting action plans are sometimes rooted in misplaced assumptions; they can facilitate elaborate ‘blame-storming’ theatre but when they address the wrong problem they are doomed to fail. I’ve attended many of these kinds of meetings wearing a technical hat, some very successful, well-chaired, with transparent and honest attempts by all parties to identify and ameliorate genuine issues between academics, technicians and students collaboratively. However, I have also attended plenty where the unspoken but clear aim was to shift responsibility for poor NSS scores into professional services teams (usually Technical Services, IT, Estates, Timetabling, Careers, and Libraries). I recall one particular meeting where the lead academic attributed high scores for teaching on their course to the lecturing team (over 50% of the course delivery was by technicians), and when challenged to respond to low satisfaction in response to the question ‘To what extent have you had the chance to explore ideas and concepts in depth?’ The cause was attributed to a printer running out of ink close to a student deadline. The resulting action plan for the following year was for technicians to fix the printer. The qualitative feedback painted a completely different picture, illuminating the actual problem with clarity, which was in no way printer-oriented. A year later, unsurprisingly, despite the printer functioning optimally, the same story played out again, and the cycle repeated without participants being bold enough to acknowledge or address the actual root cause of student dissatisfaction.

The same is true of the question ‘How well organised was your course?’ It’s common to find debates about performance and action plans that look outwards, targeting improvements in timetabling, IT, and other areas. The professional services departments indeed have a significant role to play in the student experience and smooth running of HEIs in a multitude of ways, but the stories underneath are invariably more complex. It may well be that the timetabling team hadn’t booked the rooms ahead of teaching, but if they didn’t receive the requirements by the agreed deadline or in the agreed format, then associated actions should address that issue rather than point fingers at the symptom rather than the cause.

These anecdotes illustrate how selective and distorted interpretations of NSS data can obfuscate causes and diffuse accountability. Though, as noted, NSS is no small beer, owning the problem can be intimidating, but it is also the first step to solving it. The good news is that there is a better way, and you can glimpse it from the first core question in the NSS: ‘How good are teaching staff at explaining things?’ Take note, it doesn’t ask how good the ‘academic’ staff are at explaining things, it asks about ‘teaching’ staff. Technicians, careers teams, librarians, and study skills tutors, are ‘teaching staff’ too. I’ve written about this a lot so that I won’t repeat it here, but you are unfamiliar with these concepts, please see a previous blog post about Technicians and the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF), here: https://www.timsavageconsulting.co.uk/technicians-and-the-teaching-excellence-framework-tef/.

I will add a sense of scale (time and money). Recent estimates suggest there are about 30,000 technicians working in UK HE. A study by Wragg et al., (2023) found that 84% of technicians (25,200 people) teach and support learning. Of this, if we assume that on average each has one day per week of scheduled contact time (say 7 hours, but it will be much higher than that for most, particularly at arts universities where contact time can be up to 30 hrs – but using 7hrs/pw balances for head count/FTE). Based on this, then it’s reasonable to speculate that every week, circa 175k teaching hours are delivered by technicians across the UK HE sector, which over a 38-week year equates to just under seven million technical teaching hours per annum. The average hourly salary for a technician including on-costs (based on a 5-year survey of jobs.ac.uk data) is around £21ph, so UK HEIs spend about £1.5 billion a year on technician teaching, and likely double that again on reactive student-facing one-to-one teaching through supporting guided and self-directed learning activities. Let’s say £5 billion per annum for round numbers. But, I should note these are deliberately conservative assumptions to illustrate order of magnitude in support of my NSS point, not a precise national account – so don’t cite me!

As Celia Whitchurch noted in her writing about the Third Space (the blurred territories between academic and professional services roles), students often neither know nor care whether the tutor standing before them is on an academic or a professional contract. As the data/estimates above illustrate, it’s increasingly likely that the teacher isn’t an academic (I know of several courses where over 70% of core curriculum is delivered via non-academics). Therefore, when a student responds to this question, they are synthesising their experiences of being taught throughout their course, based upon a combination of academic, technical, and professional support staff. It seems reasonable and proportionate then, that to improve the experiences that underpin the metrics, these same staffing groups should be developed and supported in a holistic and inclusive approach to the students’ experience and education.

Put simply, it is better for everyone in HE when the student experience is conceptualised as the combined experience of all who enable, teach and support learning. But, as I noted in the introduction to this post, technicians, and other professional services teams who directly influence and impact the student experience often remain routinely absent from NSS narratives, action plans, and institutional learning teaching strategies and cultures. This omission is a huge structural and strategic blind spot that inhibits the release of untapped potential to improve the student experience and corresponding NSS scores. Not least, because the staff experience is directly related to the student experience.

Timing matters

The NSS runs from January to April, with results published later in the year. That timeline can mask the fact that reported experiences don’t just run over the four months that the survey is open; instead, they’re formed over the entire course, intensifying in the final year. Experiences that unfold during that learning journey compound and leave lasting ‘impressions’ that will ultimately guide the student’s ‘expressions’ when they complete the survey. It starts with induction, and then every day and each interaction is a tile in the mosaic that comprises the picture of the cumulative student experience. Over time minor inconveniences can amount to significant dissatisfaction, for example, the moment a student can’t access equipment when they need it, or a system doesn’t work, or the 20 seconds it takes for someone to be treated like an inconvenience instead of a learner.

The technician contribution is hiding in plain sight

In my work, I use a simple framework for how technical teams contribute to learning: we enable, support, and deliver learning (this conceptualisation will also feature in the upcoming revised changes to the HESA Staff Record following the formal public consultation – more details will be coming later in the year that I will expand upon in a future blog).

- Enabling is the learning environment: spaces, kit, materials, systems, safety, digital ecosystems, navigating timetabling realities.

- Supporting is the often-invisible pedagogy of guidance, troubleshooting, scaffolding, reassurance, and “How can I…?” moments.

- Delivering is the formal teaching: inductions, demonstrations, workshops, tutorials, structured sessions, and teaching the core curriculum.

Now re-read the NSS through that lens, and it becomes obvious: technicians influence far more than “resources” questions. We affect perceptions of teaching, organisation, communication, academic support, learning opportunities, and student voice. Students don’t experience universities in organisational charts. They experience them in daily interactions with all of those who teach and support their learning.

The issue isn’t technician impact. It’s technician visibility and agency

Most technicians don’t need convincing that their work matters (it clearly does). What they need is a route to translate what they already do into:

- a shared institutional language,

- evidence leadership will recognise, and

- practical actions that don’t just add workload.

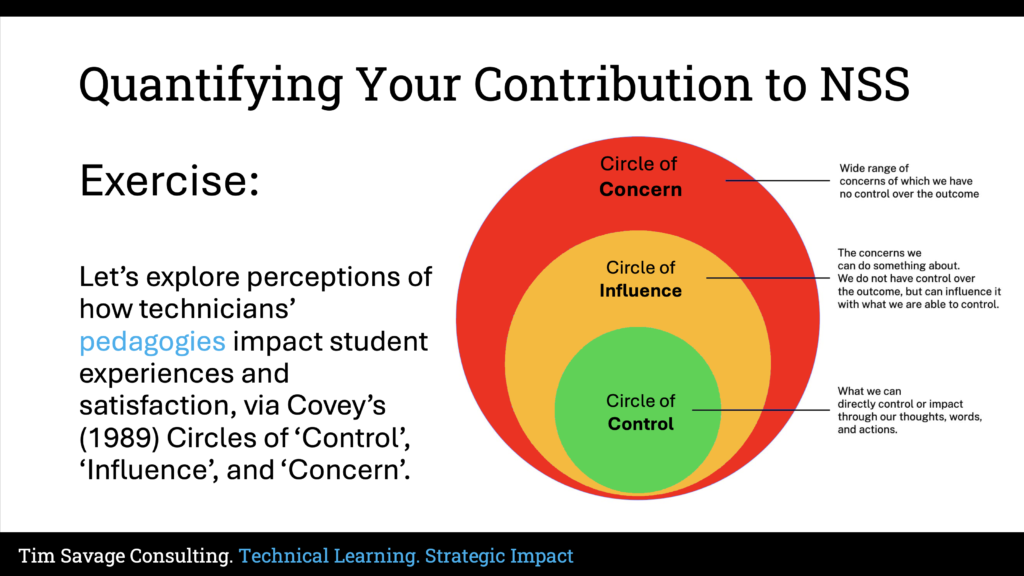

In my NSS training, I use Covey’s circles of control, influence, and concern to help technicians understand how their philosophies, behaviours, and actions shape the student experience. I use this model because it stops NSS from becoming either (a) something technicians feel blamed for or (b) something technicians feel they have no part of. Instead, it becomes:

- Control: what we can change tomorrow in our own practice and environments

- Influence: what we can shift through relationships, comms, processes, and expectations

- Concern: what we should understand to assist those in control, but not expend energy owning alone.

That mindset shift is small, but it’s powerful because it turns NSS from “something done to us” into a shared performance benchmark in a culture of student-centred continuous improvement, where both best practices and requirements for improvement can be shared honesty, authentically, and collaboratively across job families to celebrate and share success, and work together towards improvement where required.

My short course: Technicians and the National Student Survey (NSS): Understanding, Interpreting and Acting on Student Experience Data.

The full course description is available here: https://www.timsavageconsulting.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/12/Technicians-and-the-NSS.pdf

I have written the course for technicians at all levels, plus technical managers/team leaders to:

- understand how NSS data is used internally and externally,

- access and interpret quantitative and qualitative results, and

- identify where technician practice shapes student perceptions and outcomes.

By the end of the course, participants will be able to:

- explain NSS purpose, structure, and importance;

- interpret and compare results over time and across providers;

- map technician contributions across question areas (teaching, organisation, resources);

- translate feedback into prioritised improvement actions;

- use NSS insight to support professional development, appraisal, and institutional impact.

Institutions that choose to develop their technical teams and connect them with the NSS can expect a shared ownership of NSS, strengthened cross-team collaboration, and turning data into actionable, evidence-led improvement, all while improving recognition and career development for technical staff (ideal evidence in support of Technician Commitment Action Planning and self-assessment reporting).

For teams who want to go further, there are optional extensions (coaching, local deep-dives, internal showcases) to move from insight to implementation.

Final thought

If the HE sector is serious about teaching excellence, efficiency, and student outcomes, we have to stop treating technicians individually and collectively as “support” reframe them as “expertise” and start treating technical learning as a strategic asset.

If you’d like to talk about running the course or about how technicians can be more meaningfully integrated into student experience or teaching excellence strategies, you can reach me at: tim@timsavageconsulting.co.uk

If you would like to make a comment on this blog post, please do so on the original LinkedIn post. Available here: https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dr-tim-savage-pfhea-b968782b_the-paradox-of-the-nss-for-professional-services-activity-7414245944558317568-BtI2?utm_source=share&utm_medium=member_desktop&rcm=ACoAAAZbg6IBl-9AP3wGw-BmopG_SAtGrQW1h_U